From Mass Imprisonment to Abolition (USP)

Initial Questions

- In how far is the prison a product of the process of civilization?

- Is the prison a success story? In how far? In how far not?

- Why is it that for many countries, it is nearly impossible to have a decent prison system? What are the costs of building and running a decent prison system? What does it take apart from money?

- What does a lack of funds, training, and attitude do to prisons and prisoners?

- There is a general complaint that jails and prisons are overcrowded, underfunded, and unfocused these days. But hasn't that always been somewhat true? What does it mean if, as a case in point, almost immediately after the first American prisons were built, the Walnut Street Jail (1790), the Auburn Prison (1819), the Western Pennsylvania Prison (1826), and the Eastern Pennsylvania Prison (1829) were full, and within a few years, they were expanded or new prisons were under construction?

- Is it true that the prison system is suffering from some basic philosophical contradictions making functionality impossible?

- Does the prison's inability to function properly suggest that there are non-official functions (Robert K. Merton) that keep an otherwise failed system alive?

- If so, can these functions be named?

- What are the legitimate functions of a prison?

- How well equipped is the prison to fulfill them?

- What would a system look like that only served legitimate purposes?

Prison Research

Protagonists

John Howard (1726-1790): Travelling some 80,000 km during the late 18th century and visiting hundreds of jails in Britain and numerous European countries including Russia, John Howard published the first edition of The State of the Prisons in 1777. It gave very detailed accounts of the prisons he had visited, including plans and maps, together with detailed instructions on the necessary improvements, especially regarding hygiene and cleanliness, the lack of which was causing many deaths. It is this work that has been credited as establishing the practice of single-celling in the United Kingdom and, by extension, in the United States.

Frank Tannenbaum (1893-1969), ex-prisoner turned professor of criminology and author of Wall Shadows (1922) as well as Crime and the Community (1938). One of the forerunners of interactionist perspectives and the labeling approach as well as of convict criminology, his statements include “No more self-defeating device could be discovered than the one society has developed in dealing with the criminal. It proclaims his career in such loud and dramatic forms that both he and the community accept the judgment as a fixed description. He becomes conscious of himself as a criminal, and the community expects him to live up to his reputation, and will not credit him if he does not live up to it” and "We must destroy the prison, root and branch. That will not solve our problem, but it will be a good beginning.... Let us substitute something. Almost anything will be an improvement. It cannot be worse. It cannot be more brutal and more useless."

Donald Clemmer (1903-1965): Donald Clemmer coined the word "prisonization" in his work The Prison Community (1940; 1958). The term refers to the process by which the psyches and behaviors of convicts are molded by the social and structural hallmarks of prison life. Clemmer suggested that prisonization not only thwarts attempts to rehabilitate convicts but also inspires behavior contrary to accepted standards of social conduct. He was neither the first nor the last to describe this philosophical flaw in the concept of legal incarceration. (His later counter-term correctionalization did not catch on.) .

Gresham Sykes (1922-1990): His 1958 book on "The Society of Captives. A Study of a Maximum Security Prison" and his description of the Pains of Imprisonment - such as the loss of liberty, goods and services, heterosexual relationships, autonomy, and security - made him a modern classic.

James B. Jacobs (*1947): James Jacobs' analysis of Stateville: The Penitentiary in Mass Society (1977) contends that modern mass society extended citizenship rights to disadvantaged groups like prisoners, resulting in changes in the structure of authority in prisons.

Pieter Spierenburg (*1948) The Emeritus professor of Rotterdam's Erasmus University and Program director of the Institute for War and Genocide Studies creatively applies Norbert Elias' theory of civilization to the history of violence and punishment. Contrary to a widespread belief that imprisonment did not become a major judicial sanction until the nineteenth century, he traced the evolution of the prison back to the early modern period and illustrates the important role it has played as both disciplinary institution and penal option from the late sixteenth century onward.

Loïc Wacquant (*1960): In his article "From Slavery to Mass Incarceration" (2002) he maintains a genealogical relationship between chattel slavery, Jim Crow, the ghetto, and mass incarceration. In his book Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity (2009), he argues that the tough on crime ideology does not correspond to any crisis in criminality, but rather responds to the attempt to control socially and economically marginalized populations.

Michelle Alexander (*1967): in her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010) this legal scholar discusses race-related issues specific to African-American males in the United States.

Sacha Darke: the co-director of the Research Centre for Equality and Criminal Justice in the Department of History, Sociology and Criminology, University of Westminster is known for his research on Brazilian prisons including the private alternative APAC. He focused on the staff-inmate-co-production of Brazilian prison order, 2017 and contributed together with M.L. Karam the chapter on Latin American Prisons (in: Yewkes et al., Handbook on Prisons, 2nd ed., 2014).

David Scott: the Senior Lecturer at the Open University publishes about punishment and the abolition of imprisonment. His publications include "Why Prison?" (2013), "Prisons & Punishment: The Essentials" (2014; with Nick Flynn), and "Against Imprisonment" (2018).

Internet Sites

- American Correctional Association

- American Friends Service Committee (a Quaker organization in correctional reform)

- Association for the Prevention of Torture

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (information on all manner of U.S. criminal justice topics)

- Federal Bureau of Prisons

- Global Prisons Research Network

- Human Rights Watch

- Incarceration rate by country

- Innocence Project

- Latin American Prison Research Group (on facebook)

- Pew Institute: Chart of the week on prison overcrowding

- The Sentencing Project

- UN Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture (SPT)

- Vera Institute (information on a number of corrections-related topics)

- World Prison Brief

Meet the Parents of Prison Policies: Penitentiaries and Plantations

Indiscriminate warehousing: jails and early prisons

In earlier times, prisons were not yet what we refer to under that name today. That is as true for medieval prisons of the 13th and 14th century (Geltner 2008) as for those in the earlier modern period. Geltner's Research led him to the following premises regarding premodern prisons:

- Punitive incarceration’ was well known to ‘medieval law and jurists’, despite conflicting with contemporary attitudes.

- The image of the medieval prison as ‘hellhole’, as viewed by both medieval and modern commentators, ‘is simply untenable’. the centrality of the prison’s urban location and its visibility and accessibility also caused medieval life outside the walls to permeate prison life. The prison’s ‘semi-inclusive nature’ and the absence of social seclusion had a positive effect by virtue of the strong daily ties with various types of connected outsiders. In sum, life in prison for most prisoners was ‘typically a more coercive version of life at large’.

The contrast between a prison in 1770 and 1870 could scarcely have been greater. In 1770, debtors and remand prisoners in the local jails often mingled together with petty offenders sent to the workhouse. In the noisy, smelly prisons where inmates were gambling, drinking beer purchased from jailers, and mingling with friends and family, there was little sign of legal authority. A century later, all this had become unthinkable.

The term "jail" refers to places of (legal) custody or detention, usually for a shorter period of time, especially for minor offenses or with reference to some future judicial proceeding. The earliest proto-states already had their lock-ups for these purposes, and the carcer Tullianum (built in the 7th century B.C.) - today known as the Mamertinum - was a good example of jails in antiquity. In the Middle Ages, jails were often integrated in city walls or towers or cellars of castle-keeps. Since punishment usually was physical (mutilation flagellation, branding, public shaming in the stocks, decapitation), jails were used for people awaiting trial or punishment. As a matter of fact, the largest element in jails often had nothing to do with criminal justice. In England, e.g., before the advent of the modern prison, debtors were the majority of inmates. Legal action taken against them by creditors kept them in overcrowded jails until they paid their debts. In Europe, the same held true for the houses of correction in the 16th and 17th centuries that were modelled after the London Bridewell and/or the Amsterdam Rasphuis. While they also held petty offenders, their focus was not on criminal punishment, but on teaching discipline to vagrants and the disorderly local poor, and they were only absorbed into the local jail facilities under the control of the local justice of the peace at the end of the 17th century.

In 1776, the same year that America declared its independence from Britain, Philadelphia's jailhouse in the Walnut Street received its first inmates, because conditions in the old High Street Jail had become untenable. The building was neat from the outside, but less attractive inside, and at first nothing indicated that it should soon serve as a turning point in the history of punishment.

Penitentiaries: the Solitary System

This turning point was the construction of an additional building in the very yard of the U-shaped Jail, a small house called the "penitentiary house" by those who approved its construction in 1790 at the initiative of the Philadelphia Society for the Alleviation of the Miseries of Public Prisons.

What follows now is a short history of prisons by Brooke S. Biggs (2009):

"Prisons were a relatively new concept in the early 1800s. Punishment for crimes had been a matter for communities until then. Some took the Hammurabian approach of an eye for an eye, and public hangings in town squares were the price for murder, rape, or even horse thievery. As a more nuanced judicial system evolved, civic leaders sought a more civilized method of punishment, and even began entertaining the idea of rehabilitation.

In 1790, Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia (built in 1773, but expanded later under a state act) was built by the Quakers and was the first institution in the United States designed to punish and rehabilitate criminals. It is considered the birthplace of the modern prison system.

The Congregate or Silent System

Newgate Prison in New York City followed shortly after, in 1797, and was joined 19 years later by the larger Auburn Prison in western New York state. All three were perhaps naive experiments in the very new concept of modern penology. They all began as, essentially, warehouses of torture. The gallows and stocks were moved inside, but little else changed. Those who survived generally came out as better-trained thieves and killers.

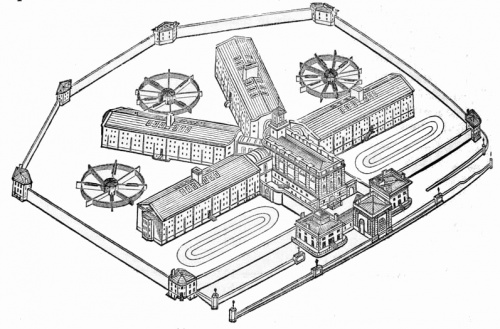

Between Philadelphia and New York, a schism in philosophies emerged: The Philadelphia system used isolation and total silence as a means to control, punish, and rehabilitate inmates; the Auburn or “congregate” system—although still requiring total silence—permitted inmates to mingle, but only while working at hard labor. At Walnut Street, each cell block had 16 one-man cells. In the wing known as the “Penitentiary House,” inmates spent all day every day in their cells. Felons would serve their entire sentences in isolation, not just as punishment, but as an opportunity to seek forgiveness from God. It was a revolutionary idea—no penal method had ever before considered that criminals might be reformed. In 1829, Quakers and Anglicans expanded on the idea born at Walnut Street, constructing a prison called Eastern State Penitentiary, which was made up entirely of solitary cells along corridors that radiated out from a central guard area.

At Eastern State, every day of every sentence was carried out primarily in solitude, though the law required the warden to visit each prisoner daily and prisoners were able to see reverends and guards. The theory had it that the solitude would bring penitence; thus the prison—now abandoned—gave our language the term “penitentiary.”

Ironically, solitary confinement had been conceived by the Quakers and Anglicans as humane reform of a penal system with overcrowded jails, squalid conditions, brutal labor chain gangs, stockades, public humiliation, and systemic hopelessness. Instead, it drove many men mad.

Sing Sing: sadistic security

The Auburn system, conversely, gave birth to America’s first maximum-security prison, known as Sing Sing (30 miles north of New York City). It differed from Walnut Street, Eastern State, and Auburn, in that inmates were permitted to speak to one another. But in many ways it was the most brutal prison ever built. Various means of torture—being strung upside down with arms and legs trussed, or fitted with a bowl at the neck and having it gradually filled with dripping water from a tank above until the mouth and nose were submerged—replaced isolation and silence.

- Nikolaus Wachsmann in his Review of The Oxford History of the Prisons: "Administrators believed that the mere denial of freedom was not punishment enough and thought up various ways of intensifying the pains of imprisonment. Their industriousness made the hand crank and the treadwheel common features in prisons of the second half of the 19th century. The latter was an especially cruel device, constructed of a series of steps on a huge wheel which was to be turned around by the prisoner's climbing motion. Not only was the work physically exhausting, but it was also mentally gruelling for the prisoners as it produced absolutely nothing. The only justification of this, in McConville's words "scarcely veiled torture" (p.147), was to punish the prisoners. A medical and scientific committee was set up in the 1860s to determine the amount of labour that could be expected from the prisoners, and after rational deliberation the experts concluded that prisoners sentenced to hard labour were to ascend 8,640 feet per day."

Sing Sing also held the distinction of being home to America’s first electric chair.

Europe’s eyes were on the curious competing theories at Sing Sing and Eastern State. A celebrity at the time, Charles Dickens visited Eastern State to have a look for himself at this radical new social invention. Rather than impressed, he was shocked at the state of the sensory-deprived, ashen inmates with wild eyes he observed. He wrote that they were “dead to everything but torturing anxieties and horrible despair…The first man…answered…with a strange kind of pause…fell into a strange stare as if he had forgotten something…” Of another prisoner, Dickens wrote, “Why does he stare at his hands and pick the flesh open…and raise his eyes for an instant…to those bare walls?”

“The system here, is rigid, strict and hopeless solitary confinement,” Dickens concluded. “I believe it…to be cruel and wrong…I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain, to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body.”

In the late 1800s, the Supreme Court of the United States began looking at growing clinical evidence emanating from Europe that showed that the psychological effects of solitary were in fact dire. In Germany, which had emulated the isolationist Pennsylvania model, doctors had documented a spike in psychosis among inmates. In 1890, the High Court condemned the use of long-term solitary confinement, noting “a considerable number of prisoners…fell into a semi-fatuous condition…and others became violently insane.”

Prisons built after this period—including Angola—were designed more as secure dormitories for captive laborers, as envisioned in the Auburn system. Inmates were required to work together at prison industries, which not only kept them occupied; it helped the institutions support themselves. Sing Sing, for example was built on a mine and constructed entirely of the rock beneath it by inmate labor.

Eastern State was a grand failure, and it was closed in 1971, 100 years after the concept of total isolation was abandoned. But what it revealed about the torturous effects of solitary may have made the practice attractive to those less concerned with rehabilitation and more interested in retribution. Solitary in the 20th century became a purely punitive tool used to break the spirits of inmates considered disruptive, violent, or disobedient. But even the most retributive wardens have rarely used it for more than brief periods. After all, a broken spirit theoretically eliminates danger; a broken mind creates it.

Ever more humane? Or have we come back full circle (and twice)?

Criminologists tended to see a linear progress in the policies of imprisonment: from indiscriminate warehousing of the 18th century to early 19th century experiments with solitary and silent systems designed to redeem the criminal sinners, going on towards the ideal and practice of social rehabilitation and re-integration of prisoners in correctional institutions ...

Today it is time to face the truth, and that gives us a different picture altogether. It seems that the pendulum has swung back. For one thing, solitary confinement has experienced a comeback that nobody would have expected only five decades ago. In some respects we are back at the days of Charles Dickens. What he had experienced in the 1840s any visitor of a communication management unit (CMU) or a supermax prison could easily witness again - if he were allowed into any of the highly secretive institutions.

Back to the Start I: The Solitary Renaissance

But in the past 25 years, the penal pendulum has swung back toward the practices—absent the theories—that governed the “Philadelphia system” invented at Eastern State. We no longer seem to have faith in the “penitent” part of “penitentiary,” and our “corrections” system no longer “corrects” anti-social behavior but inevitably breeds it. It can be argued that today, almost all maximum-security prisoners in America are kept in a kind of solitary for a large portion of their sentences. The advent of “supermax” and “control unit” prisons in the early 1970s has led to the construction of pod-based prisons and “security housing units” in which all inmates are isolated one to a cell for most of every day. They are generally allowed out for an hour each day for exercise or a shower, and are permitted limited personal possessions and visits. Many of the newer prisons enforce the “solitary” aspect by keeping some prisoners in soundproof cells, so they cannot even talk or shout at one another. The lack of regular human contact is still considered inhumane by many rights advocates who have taken to the state legislatures and courts to challenge its constitutionality. Ironically, one of the loudest advocate groups is the National Coalition to Stop Control Unit Prisons—a project of the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker group."

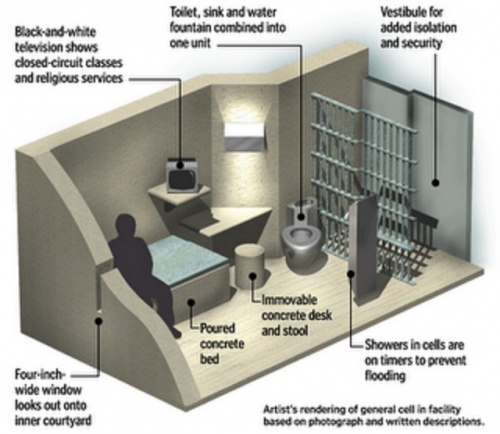

The renaissance of solitary confinement can be studied at the supermax at Florence, Colorado, the A.D.X. Florence, operated by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Prisons. (Most U.S. states also have either a supermax section or an entire supermax prison facility, but the A.D.X. Florence is considered to be on top of them all. A.D.X. Florence has a standard supermax section where inmates are kept under normal supermax conditions of 23-hour confinement and abridged amenities, and an "ideological" ultramax part, which features permanent, 24-hour solitary confinement with rare human contacts or opportunity to earn better conditions through good behavior.

- A.D.X. Florence is known for its harsh conditions; inmates are kept in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day. The hour they are allowed out is into a bigger cell with vaulted ceilings called the “empty swimming pool.” This room has a 4-inch by 4-foot skylight as the only window. It is designed to prevent the prisoners from knowing where they are, and they still spend this time alone. For at least the first three years, prisoners are not allowed to come into contact with other prisoners at any time – anywhere on the premises. Over time, good behavior can earn inmates more “outside” time, and for the most fortunate a possible transfer back to a less-secure prison can await.

- Inmates must wear leg irons, handcuffs and stomach chains when taken outside their cells -- and be escorted by guards. A recreation hour is allowed in an outdoor cage slightly larger than the prison cells. Inside the cage, only the sky is visible.

A 2012 class action suit against the Bureau of Prisons said "years of isolation, with no direct, unrestrained contact with other human beings" leave some ADX inmates -- particularly those with serious mental illness -- with "a fundamental loss of even basic social skills and adaptive behaviors." They "predictably find themselves paranoid about the motives and intentions of others." - "Once placed into unrestrained contact with other, similarly impaired and paranoid men, the stress on prisoners -- even those with no mental illness -- can be extreme. Assaults and stabbings are common." Many ADX prisoners "interminably wail, scream and bang on the walls of their cells," the lawsuit said. "Some mutilate their bodies with razors, shards of glass, sharpened chicken bones, writing utensils, and whatever other objects they can obtain. A number swallow razor blades, nail clippers, parts of radios and televisions, broken glass, and other dangerous objects."

In a maximum security prison or area (called high security in the federal system), all prisoners have individual cells with sliding doors controlled from a secure remote control station. Prisoners are allowed out of their cells one out of twenty four hours (one hour and 30 minutes for prisoners in California). When out of their cells, prisoners remain in the cell block or an exterior cage. Movement out of the cell block or "pod" is tightly restricted using restraints and escorts by correctional officers.

There is also a renaissance of torture and secret prisons, so-called black sites, often operated by secret services such as the CIA and their counterparts in other countries. A gruesome report of torture practices there can be found here.

- In January 2002, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said the prison camp was established to detain extraordinarily dangerous people, to interrogate detainees in an optimal setting, and to prosecute detainees for war crimes. In practice, the site has long been used for indefinite detention without trial.

The Department of Defense at first kept secret the identity of the individuals held in Guantanamo, but, after losing attempts to defy a Freedom of Information Act request from the Associated Press, the U.S. military officially acknowledged holding 779 prisoners in the camp. The facility is operated by the Joint Task Force Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO) of the United States government in Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. Detention areas consisted of Camp Delta including Camp Echo, Camp Iguana, and Camp X-Ray, which is now closed.In 2008, the Associated Press reported Camp 7, a separate facility on the naval base that is considered the highest security jail on the base, and its location is classified. It is used to house high-security detainees formerly held by the CIA.

In January 2010, Scott Horton published an article in Harper's Magazine describing "Camp No", a black site about a mile outside the main camp perimeter, which included an interrogation center. His description was based on accounts by four guards who had served at Guantanamo. They said prisoners were taken one at a time to the camp, where they were believed to be interrogated. He believes that the three detainees that DoD announced as having committed suicide were questioned under torture the night of their deaths.

From 2003 to 2006, the CIA operated a small site, known informally as "Penny Lane," to house prisoners whom the agency attempted to recruit as spies against Al-Qaeda. The housing at Penny Lane was less sparse by the standards of Guantanamo Bay, with private kitchens, showers, televisions, and beds with mattresses. The camp was divided into eight units. Its existence was revealed to the Associated Press in 2013. Lord Steyn called it "a monstrous failure of justice," because "... The military will act as interrogators, prosecutors and defense counsel, judges, and when death sentences are imposed, as executioners. The trials will be held in private. None of the guarantees of a fair trial need be observed."

Opinions about these prisons vary similarly to those expressed in the early 19th century concerning the Philadelphia system. Among politicians, bureaucrats, and the general public, there is a certain contentment about the security level, whereas liberal intellectuals and human rights advocates decry conditions as inhumane. In the 1820s to 1840s, officials (such as Tocqueville and Beaumont) praised the solitary system and politicians adopted it for their territories, and voice like that of Karl Marx or Charles Dickens denouncing the system as hellish remained a minority.

Today, things resemble those early reactions. There are a few liberal voices against the renaissance of solitary confinement, but as far as Realpolitik is concerned, those facilities are expanding and sometimes even seem to enjoy sufficient popular support.

A New York Times editorial argued that Guantánamo was part of "a chain of shadowy detention camps that includes Abu Ghraib in Iraq, the military prison at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan and other secret locations run by the intelligence agencies" that are "part of a tightly linked global detention system with no accountability in law."

In May 2006, the UN Committee Against Torture condemned prisoners' treatment at Guantánamo Bay, noted that indefinite detention constitutes per se a violation of the UN Convention Against Torture, and called on the U.S. to shut down the Guantánamo facility. - N.B.: Michael Lehnert, who as a U.S. Marine Brigadier General helped establish the center and was its first commander for 90 days, has stated that was dismayed at what happened after he was replaced by a U.S. Army commander. Lehnert stated that he had ensured that the detainees would be treated humanely and was disappointed that his successors allowed harsh interrogations to take place. Said Lehnert, "I think we lost the moral high ground. For those who do not think much of the moral high ground, that is not that significant. But for those who think our standing in the international community is important, we need to stand for American values. You have to walk the walk, talk the talk." Even in the earliest days of Guantánamo, I became more and more convinced that many of the detainees should never have been sent in the first place. They had little intelligence value, and there was insufficient evidence linking them to war crimes. That remains the case today for many, if not most, of the detainees.

Another recent development is the (secretive) establishment of so-called Communication Management Units (CMU) within larger prison facilities. CMUs are a type of self-contained group within a federal prison in the USA that severely restricts, manages and monitors all outside communication (telephone, mail, visitation) of inmates in the unit - have existed since 2006 in the U.S.A.. - Civil liberty and human rights groups immediately questioned the constitutionality and stated that the provisions were so broad that they could be applied to non-terrorists, witnesses and detainees. The bureau appeared to abandon the program, but on December 11, 2006, a Communication Management Unit (CMU) was quietly implemented at Indiana's Federal Correctional Complex, Terre Haute. "From April to June 2010, the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) opened up a period for public comment around the establishment of two Communications Management Units” with several civil rights groups and advocates “coming together to urge the federal Bureau of Prisons to close the experimental prison units.” It is unclear who authorized the program; it was either the Justice Department Office of Legal Counsel, FBOP Director Harley Lappin or Alberto Gonzales, United States Attorney General. It is mainly thanks to investigative journalist Will Potter that part of the public has become aware of these institutions.

Back to the Start II: The Return of Indiscriminate Warehousing (and worse)

Supermax and torture sites are not the whole picture. There are also "normal prisons", minimum security prisons, halfway houses, and even prisons "where inmates are treated as people", sometimes referred to as resort prisons.

Resort prisons

A famous example for a so-called resort prison is Bastøy in Norway. A prison on an island with no walls, no barbed wire, no electronic surveillance, no weapons, no handcuffs - just wooden cottages instead of jail cells, and dinner ranging from chicken to salmon prepared by inmates themselves. At first glance that may seem like a criminal’s distant fantasy, but in Oslo, Bastøy prison—which sits on an island 80 kilometres from the capital —offers a new perspective on how to treat criminals.

Both the supermax and the super-resort prisons are the extreme ends of the carceral continuum.

What lies in-between those extremes?

Large Run-Down Prisons (LRDPs)

In countries with a marked slaveholder past, the "normal" prisons are likely to be rough. In ex-colonial countries with little development, colonial institutions are likely to be still in use, but in a rundown version because of lack of funds and care. For many and maybe most of the 10 million plus prisoners in today's world, a likely fate is being incarcerated in what might be called one of those "large run-down prisons. We can call them LRDPs for matters of convenience. A vivid description of an LRDP from Manila would probably apply to many other of its kind in other parts of the world:

Quezon City Jail, Manila, Philippines (2016): "Every available space is crammed with yellow T-shirted humanity. The men here -- and almost 60% are in for drug offenses -- spend the days sitting, squatting and standing in the unrelenting, suffocating Manila heat. Their numbers are climbing relentlessly. At the beginning of the year, a little under 3,600 were incarcerated. In the seven weeks since Duterte took office and charged his No. 1 cop, Ronald Dela Rosa, with cleaning up the country, that number has risen to 4,053. The Quezon City Jail was built in 1953, originally to house 800 people, according to the country's Bureau of Jail Management and Penology standards. The United Nations says it should house no more than 278. There are only 20 guards assigned to the mass of incarcerated men, some of whom have been living behind these walls for years without ever seeing the inside of a courtroom. Dela Rosa earlier told CNN that the criminals in the jails and prisons would just have to squeeze in, gesturing by pulling in his shoulders and arms. Inmates are woken at 5 a.m. before undergoing a head count -- no easy task when you have 4,000-plus men crammed into crumbling, ramshackle cells.

Malignant LRDPs

Some LRDPs add some intentional cruelty. Examples for such Malignant Large Run-Down Prisons (MLRDPs) - which tend to escape attention because of their location outside the OECD world - abound.

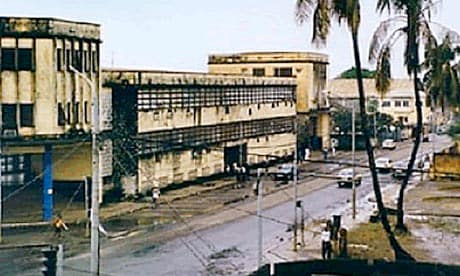

Black Beach prison in Bioko, Equatorial Guinea, is one of them. But similar conditions can be found all over Africa (from Egypt to Zimbabwe), in large parts of Asia, and Eastern Europe. In MLRDPs like Black Beach, both arbitrary and systematic torture are everyday phenomena. Prisoners are often savagely beaten, then denied medical attention. They're provided with laughable excuses for meals; some inmates starve to death. Disease spreads easily because prisoners are not given the opportunity to properly clean themselves. Prisoners are kept inside of their cells, shackles and all, for most of the day. (A number of the prisoners kept at Black Beach were members of a failed 2004 coup d'état against President Teodoro Obiang Nguema, a former Governor of this very prison).

- Thailand also has the highest incarceration rate in Southeast Asia, jailing 425 out of every 100,000 people, according to the report by the International Federation for Human Rights: More than 260,000 inmates are incarcerated in 148 prisons with an originally estimated capacity of less than 120,000, the report said, with the massive overcrowding forcing inmates to live in harsh conditions. Most prisoners were convicted on drug-related charges, the legacy of a war on drugs launched by former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra in 2003. Under Thai law, possession of heroin or methamphetamine is punishable by up to 10 years in prison. The overcrowded conditions are made worse by high turnover among guards, forcing prisons to rely on skeleton staffs, said the Paris-based human rights group. - Prisoners told interviewers from the rights group that overworked guards would beat them with clubs, throw them in solitary confinement, or keep them chained and shackled for weeks, despite government initiatives in 2013 to end the practice. - With too many prisoners, inmates can find themselves stuffed into packed cells with no beds and squat toilets with no enclosures for privacy. At night, they lie pressed against each other on mats on bare linoleum floors. "The claim made by the Thai government that the country's prison conditions conform with international standards is ludicrous," said Dimitris Christopoulos, president of the International Federation for Human Rights. (2017)

Mass Incarceration

The reality of prisons today is that they operate less in the rehabilitative mode of Quaker ideals than in a retributive mode that has long been practiced and promoted in the South of the USA (and in other countries that are still carrying the burden of their slaveholder society past). In those ex-slaveholder societies, at least, prisons trace their lineage back not so much to the penitentiaries, but to slave plantations and the brutal repression exercised by white masters over non-white others. White supremacy is the underlying principle, and racial domination is the real end of it all. As Michelle Alexander says: "The system of mass incarceration works to trap African Americans in a virtual (and literal) cage." In the United States, blacks are incarcerated seven times as often as whites. As Adam Gropnik summarizes in his wonderful article on The Caging of America (2012):

- "Young black men pass quickly from a period of police harassment into a period of 'formal control' (i.e., actual imprisonment) and then are doomed for life to a system of 'invisible control'. Prevented from voting, legally discriminated against for the rest of their lives, most will cycle back through the prison system. The system, in this view, is not really broken; it is doing what it was designed to do."

Michelle Alexander: "If mass incarceration is considered as a system of social control - specifically, racial control - then the system is a fantastic success."

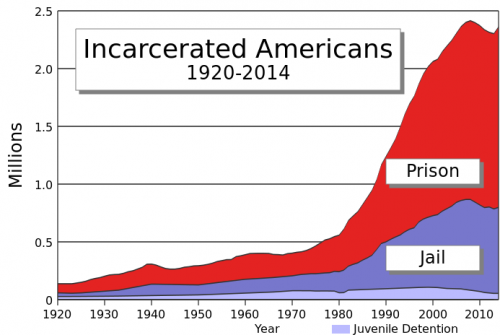

Whether called mass incarceration, mass imprisonment, the prison boom, the carceral state, or hyperincarceration, this phenomenon refers to the current American experiment in incarceration, which is defined by comparatively and historically extreme rates of imprisonment. Mass incarceration is a term used to describe the substantial increase in the number of incarcerated people in the United States' prisons over the past forty years. The prison population of the United States dwarfs the prison populations of every other developed country in the world. In the U.S., every speech, every op-ed, every white paper about criminal justice starts with the same data points: The U.S. has 5% of the world's population and 25% of the world prisoners, more prisoners than soldiers, more correction officers than marines, more prisons than Walmarts.

Countries with high incarceration rates

- Seychelles 799. Until 2016, the Seychelles were the world's number one incarcerating nation with a peak at 799 per 100,000 inhabitants. Only that they never did have as many inhabitants. The Seychelles were used as a depository for Somalian pirates, but most imprisonment - experts spoke of 70% - had to do with drug-related offenses. A kind of mass amnesty that set 150 drug offenders free let the rate drop well below the 500 mark, but since the tough drug laws of the country have simultaneously been further stiffened, things might soon return to the old normal.

- United States of America 693 - The U.S. incarceration rate fell from 690 to 670 per 100,000 people, which is still higher than that of any country (except Seychelles, one had to add for accuracy until recently). Drug offenders account for half of federal prisoners and 16 percent of state prisoners. A decrease in the federal prison population was largely due to shorter drug sentences]

- St. Kitts and Nevis 607 - The islands serve as a transhipment point in the transnational drug trade

- Turkmenistan 583 - High rate due to ruthless punishment of any alternative political or religious expression. Presumably, prisons also hold many people who forcibly disappeared. Torture to extract “confessions” and incriminate others is common in spite of recent anti-torture legislation. Sources describe the use of dogs, batons, and subsequent loss of consciousness, damage to the kidneys, and the inability to walk. So-called kartsers or cylindrical dark solitary confinement cells can be the location of people before or after secret trials, and family members often do not receive information whatsoever.

- Virgin Islands (U.S.) 542 - Justice Department officials are so fed up with a drug-infested, violence-wracked prison in the U.S. Virgin Islands they did something they had never done before -- they went to court and asked to entirely take over operation of the institution. The request for a federal judge in St. Croix to appoint a federal receiver came as stabbings, firearms and filth mounted at the Golden Grove Adult Correctional and Detention Facility. "The deplorable conditions at Golden Grove continue to deteriorate after years of noncompliance with court orders," said Assistant Attorney General Thomas Perez. "This agency has left us with no choice but to seek the drastic measure of receivership," Perez said. "Receivership is the last resort," said U.S. Attorney for the Virgin Islands Ronald Sharpe. "We arrive at this juncture only after spending the last 25 years exhausting every other viable alternative," he said. Justice Department officials said the prisoners live in unsafe, filthy and hazardous conditions without required medical and mental health care.

- El Salvador 541 - A plague of fungal skin diseases, untreated deadly infections, constant threats of tuberculosis epidemics, people fed with their own hands, extreme overcrowding and children locked up with their mothers. This is what the human rights observers reported during the first few months of the extraordinary measures implemented across prisons for El Salvador’s gang members. - The Attorney General’s Office is the only institution that has access to these prisons under these extraordinary measures. The government has decided to deny access to the public, including the International Committee of the Red Cross. - “The fact that they are served food in their hands is…inhumane. The overcrowding…all in the same cell for 24 hours! It’s like…the torture facilities of the past. You would think that all of that was over. You would think that Hitler was a thing of the past. Once the doors are opened, what will we see?” - The statement was from Raquel Caballero, of El Salvador’s Attorney General’s Office for Human Rights (Procuradora para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos – PDDH), who was left speechless as she tried to describe what she saw in the prisons where the government’s extraordinary measures have been implemented. - In April 2016, the government implemented extraordinary measures for seven Salvadoran prisons where only gang members are detained. The aim was to isolate certain prisoners with the understanding that they were the momentum driving gang criminality. In order to do this, the government eliminated family visitation; confined prisoners to their cells 24 hours a day; halted the delivery of hygiene products like soap, toilet paper and toothpaste; suspended judicial proceedings and restricted maximum-security prisoners from being released to hospitals. restricted street clothing and electronics....

- Cuba 510 - Cuba refuses access to the Red Cross, calling that interference in internal affairs. But they know they can't open up fully to international scrutiny, because people would be horrified,

- Guam (U.S.) 469 - For twenty-three years a federal receiver has overseen Guam's troubled correctional system, but unfortunately for prisoners, medical care still appears to be substandard. According ... Also contributing to prisoner health problems are the issues of chronic overcrowding and staff shortages in all departments.

- Russian Federation 450 - Overcrowding in prisons is especially conducive to the spread of tuberculosis; according to Bobrik et al., inmates in a prison hospital have 3 meters of personal space, and inmates in correctional colonies have 2 meters. Specialized hospitals and treatment facilities within the prison system, known as TB colonies, are intended to isolate infected prisoners to prevent transmission; however, as Ruddy et al. demonstrate, there are not enough colonies and isolation facilities to sufficiently protect staff and other inmates.

- Thailand 445 - A woefully inadequate prison infrastructure characterized by overcrowding and corruption. Rayong Central Prison, designed for 3,000 inmates, holds 6,000, and corrupt prison officials further complicate the situation. In a sting operation some 28 prison wardens were found to be smuggling drugs. A new super-max prison is planned.

Minorities

- More black males are in prison than are enrolled in colleges and universities. In 2000 there were 791,600 black men of all ages in prison and 603,032 enrolled in college (a dramatic change since 1980, when there were 143,000 black men of all ages in prison and 463,700 enrolled in college.) In 2003, according to Justice Department figures, 193,000 black college-age men were in prison, while 532,000 black college-age men were attending college. On an average day in 1996, more black male high school dropouts aged 20–35 were in custody than in paid employment; by 1999, over one-fifth of black non-college men in their early 30’s had prison records.

Roots of Mass Imprisonment

- Increase in drug related inmates because of (1) expanding drug market, (2) pro-active anti-drug policies, (3) counterproductive results of kingpin-strategy (DEA)

- High admission rate (percentage of offenders receiving a prison sentence) and longer length of stay (resulting from longer sentences) - The Sentencing Project;List of longest prison sentences

- Sentencing Guidelines; minimum sentences: These longer sentences, coupled with the fact that drug offenses are the most common offenses carrying mandatory minimum penalties, considerably affect the prison population. At the end of 2016, nearly half of all U.S. federal inmates were drug offenders and nearly three-quarters of those drug offenders in prison were convicted of an offense carrying a drug mandatory minimum penalty. The data also demonstrates that the effects of mandatory minimum penalties on sentencing occur for drug offenders across the culpability spectrum and regardless of an offender’s role in the offense.- In fiscal year 2016, over half (52.8%) of offenders convicted of an offense carrying a drug mandatory minimum penalty faced a mandatory minimum penalty of ten years or greater.

- Draconian legislation (death penalty states from 10 to 33), penal populism

- Sociology of punitiveness: social control of the economically useless masses (=dangerous classes)

- How Can a Public Tolerate It? (1) Normative Preponderance (clawback), (2) Lacking sense of togetherness (Randolph Roth, American Homicide)

- Surveying the last 200 years of the history of the prison, one might well ask why the constant failure of the prison to live up to its claims has had no impact on its continuing longevity. The history of the prison emerges as a succession of phases of over-exaggerated optimism in the power of the prison to change human behaviour, swiftly followed by failure in the realm of reality.

Three quarters of people who are released from prison will be arrested within five years and about 55 percent will end up back in prison —Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2014.

One explanation for the survival of the prison might be that it has been successfully presented as the embodiment of a variety of contradictory justifications for punishment: it can been seen as incapacitating, retributive and as educative; either as harsh punishment or as benevolent reform, whichever suits the public mood best. - No research has been able to demonstrate a positive link between a higher rate of imprisonment and a reduction of the crime rate.

In fact, as Norval Morris points out in Rothman and Morris (1995), the less effective the prisons are in reducing crime, the higher the demand for more imprisonment.

The view persists that increased severity of punishment will lead to less crime. In this context, the prison has also become a weapon in politics. As Morris observes, being "tough on crime" today is a precondition for election to public office, and imprisonment remains the preferred way of demonstrating this resolve in the never ending but constantly proclaimed "war on crime". As long as this naive belief in the powers of the prison is not put into perspective by its history of failed promises, the rallying cry of politicians in Britain and the US will continue to be "prison works" - irrespective of which party they belong to.

Violence

- Competitive violence: inmates vs. inmates and gangs vs. gangs. That can be individual, but also collective. Prison gangs engage in "war making," or monopolizing on force and occupying the power vacuum of state authority. They eliminate rivals within their territories, and in doing so they carry out "state making." Gangs offer protection to their members, affiliates, and clients. Example: The Primeiro Comando da Capital (or the PCC) is a Brazilian prison gang based in São Paulo. The gang rose in 1993 at a soccer game at Taubate Penitentiary to fight for prisoners' rights in the aftermath of the 1992 Carandiru Massacre. The PCC orchestrated rebellions in 29 São Paulo state prisons simultaneously in 2001, and since then it has caught the attention of the public for ensuing waves of violence. The Brazilian police and media estimate that at least 6,000 members pay monthly dues and are thus a base part of the organization. According to São Paulo Department of Investigation of Organized Crime, more than 140,000 prisoners are under their control in São Paulo. The statutes of the PCC do not allow mugging, rape, extortion, or the use of the PCC to resolve personal conflicts. It maintains a strict hierarchy, led by 50 year old (2018) Marcos Willians Herbas Camacho (Marcola), who presently serves a 234 year prison sentence at Presidente Venceslau, S.P. - All members inside and outside are required to pay taxes. Members can be soldiers, towers (gang leaders in particular prisons), or pilots (who specialize in communications). -- According to political scientist Benjamin Lessing crackdowns and harsher carceral sentences often just increase prison gangs' control of outside actors and lessen state power: "the harsher, longer, and more likely a prison sentence, the more incentives outside affiliates have to stay on good terms with imprisoned leaders, and hence the greater the prison gangs' coercive power over those who anticipate prison." - At the turn of 2016/17, just days after prison clashes between rival gangs killed 56, it was reported that at least 33 inmates had were killed in northern Roraima state.

- Repressive violence: officials vs. inmates. Example: Friday, 2 October 1992, military police stormed Carandiru Penitentiary in São Paulo, Brazil, following a prison riot after a soccer game. By the end of the day, 111 prisoners were dead; and 37 more were injured. Gunshot wounds were mainly found in the face, head, throat and chest. Hands among the dead were found in front of the face or behind the head suggesting defensive positions. Police were also reported killing witnesses, wounded prisoners, and even those forced to remove bodies. No policeman was injured. Evidence suggests that many prisoners were, defenceless and intentionally extrajudicially executed.

- Revolting violence: inmates vs. officials. Heather Ann Thompson (2016) Blood in the Water. The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. - As an indirect result of the Attica uprising, the New York State Department of Corrections 1) began a grievance procedure, in which inmates could grieve (object to) actions by a staff member that violated stated policy, 2) started at each prison a program under which the warden and other senior management meet on a monthly basis with elected representatives of the inmates, and 3) began allowing packages to inmates to be received year-round. - Revolting violence can have a containment effect on repressive violence as in the case of the Brazilian PCC. See Graham Denyer-Willis (2015) The Killing Consensus: Police, Organized Crime, and the Regulation of Life and Death in Urban Brazil. Durham: Duke University Press.

Prison massacres are a recurrent phenomenon, says Gianfranco Graziola of the Pastoral Carcerária (Brasil)

To prevent torture in prison the best way would be to prevent prison.

Beyond Imprisonment

Here, the carceral continuum in the minimum security state will dispense of the prison. As Gilles Deleuze said in his Postscript on the Control Society:

- "We are in a generalized crisis in relation to all the environments of enclosure–prison, hospital, factory, school, family. The family is an “interior,” in crisis like all other interiors–scholarly, professional, etc. The administrations in charge never cease announcing supposedly necessary reforms: to reform schools, to reform industries, hospitals, the armed forces, prisons. But everyone knows that these institutions are finished, whatever the length of their expiration periods. It’s only a matter of administering their last rites and of keeping people employed until the installation of the new forces knocking at the door. These are the societies of control, which are in the process of replacing disciplinary societies. “Control” is the name Burroughs proposes as a term for the new monster, one that Foucault recognizes as our immediate future. Paul Virilio also is continually analyzing the ultrarapid forms of free-floating control that replaced the old disciplines operating in the time frame of a closed system. There is no need to invoke the extraordinary pharmaceutical productions, the molecular engineering, the genetic manipulations, although these are slated to enter the new process. There is no need to ask which is the toughest regime, for it’s within each of them that liberating and enslaving forces confront one another. For example, in the crisis of the hospital as environment of enclosure, neighborhood clinics, hospices, and day care could at first express new freedom, but they could participate as well in mechanisms of control that are equal to the harshest of confinements. There is no need to fear or hope, but only to look for new weapons."

Everyday surveillance, pre-penal control and sanctions (Gefährder, sub-criminal anti-social behaviour), degrees of non-custodial and custodial sanctions (including pre-trial detention), post-custodial surveillance. - Net-widening, non-custodial alternatives to imprisonment. Restorative Justice.

The World of the New Helots

- "In the nineteenth century the Industrial Revolution created a huge new class of urben proletariats, and socialism spread because no other creed managed to answer the unprecedented needs, hopes and fears of this new working class. Liberalism eventually defeated socialism only by adopting the best parts of the socialist programme. In the twenty-first century we might witness the creation of a massive new unworking class: people devoid of any economic, political or even artistic value, who contribute nothing to the prosperity power and glory of society. This 'useless class' will not be merely unemployed - it will be unemployable" (Harari 2016: Homo Deus, 379).

- Legal and extralegal control: run-down prisons, camps, disease

- Return to the Times of John Howard: Wheelbarrow Men, Torture, Overcrowding, Disease

- Competing and shared sovereignty (gangs and the state): parallel justice

Instead of Prisons

Reduction

- Criminal Justice Reinvestment

- Restorative Justice

- Community Work

- Alternative Sentences

Abolition

1. Overcoming the cell prison - and punitive deprivation of liberty.

- International Conference on Penal Abolition (IOPA)

- No Prison (Europe)

- Catherine Baker (*1947) argues for the complete abolition of the prison system in her booklet Pourquoi faudrait-il punir?" (2005)

- "J'ai toujours pensé que l'enfermement était absurde; ma claustrophobie y est sans doute pour quelque chose. Mais par principe aussi : nécessaire sans doute mais inopérant. Une oeuvre de destruction. L'abolition de tous les repères. Quoi qu'un homme ait pu faire, il mérite mieux. Punition oui, en prison non. Cours de droit pénal classique : la peine sert à punir et à réinsérer (tout cela sur fond de disputes théoriques). Cette formule se vérifie rarement, malheureusement. Et les abolitionnistes sont de plus en plus nombreux; ils triompheront un jour. Alors, il faudra approfondir les peines alternatives à la privation de liberté; comme la médiation et la méditation (n'est-ce pas le rôle des nombreuses commissions Vérité et réconciliation ? cf. Catherine BAKER, Pourquoi faudrait-il punir ? Sur l’abolition du système pénal, pp. 151-173). Le paradigme de l'écoute : juste s'arrêter un instant pour tendre l'oreille : "allez raconte-nous pourquoi tu as fait cela ?".

- Michel Onfray and others published a Manifesto (in English, French, and Greek) calling For the Abolition of Every Prison and the Logic of Incarceration.

- The philosophers Michel Onfray and Tony Ferri, the MP Noël Mamère, the ex-president of the International Prison Observatory Gabriel Mouesca, the lawyers Lucie Davy and Yannis Lantheaume and the ex-prisoner Philippe El Shennawy sign this manifesto and demand this archaic system that allows “the imprisonment of human by human to be thrown in the deepest dungeons of history”.

- “Prison was built on the principles of philanthropy: during the time of their incarceration, the offenders would reflect, would improve, would be reborn. History defeated this sad nonsense. A prison can only be constructed on the foundations of absolute spiritual cruelty; otherwise imprisonment is just based on the hope that everything will go well after it ends, hence on something completely inconceivable”. When Catherine Baker (journalist of the libertarian movement, author and supporter of the abolition of prisons) was writing these words in March of 1984, in France there were 38,600 persons held in prisons. Thirty years later this number has increased to 69,000 and the average time of incarceration is more than double (from 5.5 to more than 12 months).

- Unable to reassure a public opinion that keeps asking for more and more security, the politics that have been implemented for half a century now, lead to the incarceration of an increasing number of people, gradually transforming the welfare State to a punishing State. The construction plans for new prisons succeed one another with a frantic speed, while their instigators keep guaranteeing the end of the chronic problem of the overcrowding of prisons and the ‘humanisation’ of the conditions of detention. In reality though, as the number of cells increases, the number of the prisoners increases accordingly. Humanisation translates into a cold, sterilised environment, intense colours and electronic surveillance systems, in replacement of the old filthiness and the unhealthy dormitories. Yet, a ‘golden’ cage is still a cage; and the prisoner –or, as they are called nowadays ‘the user of public penitentiary services– remains a hamster in a cage. There is nothing, or almost nothing that the prisoner can do for the time to pass. They are occasionally offered a repetitive and underpaid job. Their correspondence? All but confidential. Their visits? Restricted, controlled and surveyed. In case of inappropriate behaviour they will be placed in the disciplinary area, a proper dungeon where the prisoner is lowered to the level of an animal. For the most indisciplined or those strictly surveyed? There is isolation, the white cell that destroys you slowly and painfully.

- The list is infinite. “There is no need to repeat the obvious: incarceration makes you insane, ill, harsh and greedy”, Catherine Baker used to write many years ago. It is something exceptionally paradoxical as “no one desires to live in a world where some people take the risk to imprison some others, constituting them even more threatening than what they actually are”.

- The basic punishment of the prisoner is the dead time that passes relentlessly. It is the sense of the loss of time that nibbles the body and the spirit. All the rest –the repletion of the cells, the isolation and the discipline– are nothing but different aspects of the issues that have as a result the slow death of those that society has rejected. The prisoners kill their time but it is actually the time that kills them. They grow old without having really lived and when they exit the prison we tend to say that they served their time. But time has corroded them; has shattered them. More than any other person, the prisoner is the carcass of time.

- When the time of their release comes, they need to learn again how to live: to regain their autonomy while for months or years they were in a state of absolute dependence, even for the most simple of movement, having lost any kind of free will and effect of their everyday lives. They have to learn again the ‘outside’ manners, while they have spent so much time in the state of the special laws of the prison system. They have to learn again how to love and touch, while for years they were deprived of any physical contact. They have to learn again how to open doors, as for years they would only see them shutting in front of them. Finally, they have to learn again how to be complete as persons, while this could be something that they never learned in the first place.

- From the international fora for human rights till the organisations dealing with prisons, through the International Prison Observatory, the General Auditor of the spaces depriving freedom or the few MPs that exercise their right to visit the prisons, the voices that denounce the conditions in French prisons increase. Nicolas Sarkozy considered them ‘a shame for Democracy’. Christine Taubira describes them as ‘numerous but empty of meaning’. And yet after all these statements we get to hear that they have to be reformed, that it is necessary and urgent to re-examine prisons, their role and target in the penal system, or event to reorganise them. “Literally speaking, reform is not unthinkable, but impossible” claims Catherine Baker: “The less the prison punishes, the less it meets its mission. Blaming the prisons for excessive punishment is like blaming a hospital for excessive curing”.

- The prison is the prime condition that we should not attempt to reform, but only to abolish. Firstly, because the penitentiary institution is such, that any progress comes with the price of the equivalent regression. Thus, the institutionalisation of ‘special conditions’ of detention would allow some prisoners, but not all of them, to detour the disciplinary process. The abolition of the prison is a choice because the prison bears in it the relentless logic of exclusion, resulting in the marginalisation and impoverishment of those who were incarcerated due to their precarious place in society or their family environment. The reform of the prison is impossible, as its inherent violence causes to those that experience it hatred and hostility towards anyone else and towards the whole of society; feelings that any social body should avoid to reproduce. Its abolition is imperative because, according to all the studies, the prison has completely failed to prevent relapse and thus causes more harm than good to society.

- But it should also be abolished because it constitutes a symbol. As a parasitic outgrowth of our societies, it seems to be the concentrated form of all evil. Isolation, solitude and separation are forced there at their maximum. Out there, the public space, urbanisation, architecture and transportation acquire more and more penitential features. Even in the outside world, work and the commercialised social relations reproduce incarceration, neurosis and desperation.

- France was the first European country to abolish torture, besides the prudent voices of the time, supporting that without it French justice would be disarmed and the good prisoners would be left in the hands of criminals. Additionally, France was one of the first countries in the world to abolish slavery, this crime against humanity that has been committed for the past 200 years. In 1981, the abolition of the death penalty (in France) reflected a social need. Even though France was one of the first Western European countries to outlaw this absolute negation of the value of human life, the result of this action was paradoxical. Without managing to solve any ethical and political problem arising in the context of human rights, the abolition of the death penalty did not end the logic of extermination that still exists in our country. Those that we nowadays call ‘convicts serving long sentences’ are nothing less than condemned to a slow death; a social death. Having been adopted in order to respond to a strong social movement where sentimentalism was fighting with hypocrisy, the abolition of the capital punishment did not mark that much the symbolic rise of the Left (with the rise of Francois Mitterrand at the presidency of the country) but the confirmation of the limits in its thinking. In any case, the end of the death penalty ended neither death (since after the last execution of a prisoner in 1977 more than 3,000 convicts have committed suicide) nor the punishments in the prisons .

- We argue that nowadays, holding a person incarcerated does not mean that you punish them: it means that you permit the perpetuation of an archaic system that is now obsolete and incompatible with postmodern societies. We demand this abhorrent practice that allows the isolation and confinement of human by human, to be thrown in the deepest dungeons of history. It is our belief that it will not be long before imprisonment is considered by humans as the most irrefutable evidence of the brutality, the moral and emotional decline that characterised humanity till the beginning of the 21st century. We deny that Justice has the right, in the name of the law, to condemn people in imprisonment.

- Alain Cangina, president of the association Renaître (consisting of ex-prisoners it intervenes and highlights cases of mistreatment in prisons); Audrey Chenu, ex-prisoner, teacher and author of the autobiographic book Girlfight; Lucie Davy, lawyer; Philippe El Shennawy, ex-prisoner; Tony Ferri, philosopher; Samuel Gautier, cinematographer; Yannis Lantheaume, lawyer; Jacques Lesage de La Haye, writer and psychologist; The unknown inmate, prisoner in a French prison and blogger under the same name; Philippe Bouvet, professor of history/geography and father of a detained person; Thierry Lodé, biologist, Noël Mamère, independent MP of the party Europe, Ecology and Green (European Green Party??), Gabriel Mouesca, historic member of the Basque separatist group Iparretarrak and ex-president of the International Prison Observatory (OIP); Yann Moulier-Boutang, economist and essay writer; Michel Onfray, philosopher; Antoine Pâris, journalist.

- Ricardo Genelhú & Sebastian Scheerer (2017) Manifesto para abolir as prisões: trata sobre a situação presente do sistema prisional no Brasil, o poder prisional e quem são seus atores, a quem e pra quem ele serve e por que ele foi inventado. Discute-se sobre o encarceramento em massa, a (não) ressocialização dos encarcerados, a teoria da less eligibility e o regime disciplinar diferenciado. E por último, faz-se um panorama sobre o futuro do sistema prisional.

2. Overcoming punishment Restorative Justice as an alternative not only to prison, but also to punishment as such.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Michelle (2012), The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, New York: The New Press.

- Ayers, Edward L. (1984), Vengeance and Justice: Crime and Punishment in the 19th-Century American South, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Biggs, Brooke S. (2009) Solitary Confinement: A Brief Natural History, in: Mother Jones

- Blackmon, Douglas A. (2008), Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, New York.

- Christianson, Scott (1998), With Liberty for Some: 500 Years of Imprisonment in America, Boston: Northeastern University Press.

- Clemmer, Donald (1940), The Prison Community. Boston: The Christopher Publishing House.

- Deleuze, Gilles (1990) Postscript on Societies of Control, in: Funambulist

- Denyer-Willis, Graham (2015) The Killing Consensus: Police, Organized Crime, and the Regulation of Life and Death in Urban Brazil. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Foucault, Michel (1995) Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison. NY: Vintage Books.

- Geltner, Guy (2008) The Medieval Prison: A Social History. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.

- Genelhú, Ricardo & Sebastian Scheerer (2017) Manifesto para abolir as prisões (2017)

- Gottschalk, Marie (2006), The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America, Cambridge.

- Harari, Yuval N. (2016) Homo Deus. A Brief History of Tomorrow. London: Vintage.

- Hirsch, Adam J. (1992), The Rise of the Penitentiary: Prisons and Punishment in Early America, New Haven.

- Howard, John (1777), The State of the Prisons in England and Wales: With Preliminary Observations, and an Account of Some Foreign Prisons. Warrington: Cadell, Conant.

- Ignatieff, Michael (1978), A Just Measure of Pain: The Penitentiary in the Industrial Revolution, 1750–1850, New York.

- Jacobs, James B. (1997), Stateville. The Penitentiary in Mass Society. With a Foreword by Morris Janowitz. Chicago: U of Chicago Press.

- Jacobsen, Jessica et al. (2017) PRISON. Evidence of its use and over-use from around the world.pdf

- Lewis, Orlando F. (1922), The Development of American Prisons and Prison Customs, 1776–1845, New York: Correctional Association of New York.

- McLennan, Rebecca (2008), The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941, Cambridge.

- PCC: Estatuto

- Rothman, David & Norval Morris, eds (1995) The Oxford History of the Prison: the Practice of Punishment in Western Society. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Spierenburg,Pieter (2007) The Prison Experience. Disciplinary Institutions and Their Inmates in Early Modern Europe. With a Preface by Elisabeth Lissenberg, Amsterdam : Amsterdam University Press.

- Prisons. Chapter 7. The State of Prisons - Transgender and useful weblinks

- Sykes, Gresham M. (1958) The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- UNODC 2017: Roadmap for Prison Based Rehabilitation Programs

- Wacquant, Loïc (2009), Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity. Durham: Duke University Press

Weblinks

Mass Imprisonment

- History of United States prison systems

- Mass Imprisonment U.S.A..

- Mass Imprisonment U.S.A. on YouTube

- Mass Imprisonment U.S.A. on YouTube 2015

- Electric Chair History (Auburn)

Resort Prisons: Bastøy in Norway

- No handcuffs, no cameras, no weapons. But decent wooden cottages on an island 80 kilometres from Oslo — a new perspective on how to treat criminals.

- Where Inmates Are Treated Like People. The Guardian (2013)

- Michael Moore on the Prison Island, YouTube

Run-Down Prisons

- Destitute-Malignant Prisons: Black Beach in Equatorial Guinea

- Large Run-Down Prison (LRDP): Quezon City Jail on YouTube

Supermax-Prisons

- Supermax: Just how bad are they? BBC (2012)

- Supermax: What's life like in a Supermax Prison? (CNN 2015)

- Communication management unit, wikipedia

- CMU TED talk Will Potter

- Will Potter: The secret prisons in the U.S.A. about communication management units.