Walnut Street

Deutsch

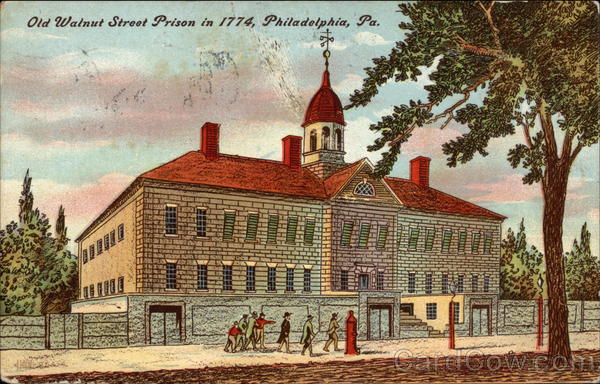

Das Walnut Street Jail - ein Gebäude des prominenten Architekten Robert Smith aus dem Jahre 1773 - diente der Stadt Philadelphia und dem Commonwealth of Pennsylvania als Orts- und Staatsgefängnis bis 1835 und wurde 1838 abgerissen. An seinem Ort steht heute eine Bibliothek. Zweck des Walnut Street Gefängnisses war es, das alte Stadtgefängnis in der High Street abzulösen, wo die Zustände unzumutbar geworden waren. Doch dem Walnut Street Gefängnis sollte dasselbe Schicksal beschieden sein. Unzumutbare Zustände führten zu seiner Schließung und Zerstörung und zum Neubau des Eastern State Penitentiary, das von 1829 bis 1971 in Betrieb war. Gleichwohl gingen entscheidende Impulse für die Entwicklung des Gefängniswesens nicht nur in den USA, sondern auch in Europa und auf der ganzen Welt vom Gefängnis in der Walnut Street aus.

In den Stadtgefängnissen pflegten unerwünschte Personen aller Art ohne Trennung nach Geschlecht, Alter, Haftgrund usw. unter erbärmlichen Bedingungen zusammengepfercht zu sein. Straftäter waren da oft eher eine Minderheit unter Geisteskranken, zahlungsunwilligen oder -unfähigen Schuldnern, Prostituierten, Vagabunden, Bettlern, Versehrten und Aufsässigen oder Schwererziehbaren aller Art. Das sollte sich erst im Laufe der Zeit ändern und insbesondere aufgrund der Aktivitäten der Philadelphia Society for the Alleviation of the Miseries of Public Prisons (gegründet 1787).

Schon kurz nach ihrer Gründung sahen die Mitglieder der Society, dass karitative Hilfe nicht geeignet war, die tieferliegenden Probleme des Gefängnisses in der Walnut Street zu beheben. Sie erreichten die Verabschiedung eines Gesetzes, das das Haus in der Walnut Street zum Staatsgefängnis machte und ihm eine völlig neue Verwaltungsstruktur gab. Vor allem aber errichtete die Society im Hof des Gefängnisses ein sogenanntes Haus des Bereuens - das sogenannte Penitentiary House. Vom Beschluss bis zur Inbetriebnahme vergingen zwar nicht zuletzt aufgrund politischer Widerstände gute fünf Jahre (von 1790 bis 1795/96). Auch war Einzelhaft zwar das Ziel des Penitentiary, doch konnte nur etwa ein Drittel der Gefangenen so untergebracht werden.

Dennoch gilt Walnut Street als Geburtsort des modernen besserungsorientierten Strafvollzugs. Von 1793 bis 1796 wurde das Gefängnis sehr erfolgreich von einer Frau geleitet. Wahrscheinlich war Mary Weed die erste und für lange Zeit einzige weibliche Anstaltsleitung. In zeitgenössischen Quellen wurde sie bei der Aufzählung des Personals als "jaileress" bezeichnet.

Auf den Prinzipien des Walnut Street Penitentiaries baute das Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP) in Philadelphia auf (1829-1971). Die besondere panoptische Architektur des ESP - strahlenförmig, bzw. wie die Speichen eines Kutschenrades angeordnete lange Blöcke - wurde zum Modell für die Anstalt Pentonville bei London (1842) und mehr als 300 Gefängnisgebäude auf der ganzen Welt.

English

The nondenominational Society for Relieving the Miseries of Public Prisons (with a commanding influence of Quaker members and later changed its name to Pennsylvania Prison Society) quickly became a leading advocate for the humane and salutary treatment of the incarcerated. From the restructuring of the Walnut Street Jail in the eighteenth century, to the construction and oversight of the Eastern State Penitentiary in the nineteenth, and its ongoing work as a social casework agency, the society’s efforts shaped correctional practices in Pennsylvania and beyond.

- Spurred by reports of deplorable conditions in Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail, the society appointed an acting committee of six to ascertain the conditions of confinement and its effect on inmates’ moral and physical wellbeing. Prison Society visitors found a chaotic institution where inmates of all types, ages, and sexes mixed indiscriminately in an environment rife with obscenity, idleness, and vice. Realizing that the direct relief offered to prisoners in the form of bibles, clothing, medical care, and cash would not address these broader problems, the society also turned its efforts toward legislative change. Proposed reforms included abolishing the use of iron shackles and establishing a set salary for the jailer to avoid corruption. The Society formed in response to stories of inhumane treatment and unsanitary conditions at the Walnut Street Jail. In 1790, the society built a new penitentiary at the prison where prisoners were expected to silently repent in private cells.

- Most significantly, the Prison Society supported the solitary confinement of all prisoners. Influenced by the writings of the British prison reformer John Howard (1726–90), the proposed “separate system” would prevent hardened criminals from corrupting first-time offenders and would provide all inmates with the space needed for serious reflection and reform. Following legislative approval in 1790 for the separation of prisoners by age, gender, and crime committed, the Walnut Street Jail and the Pennsylvania Prison Society became models for prison reform efforts throughout the United States and in Europe.

In 1787, the Society for the Alleviation of the Miseries of Public Prisons was founded for that exact purpose by prominent citizens. In 1790, the Society - weary of the limits of social work - succeeded to pass legislation that would transform the 1773 Walnut Street Jail (first prisoners 1776) into a state prison. The first step was the construction of a Penitentiary House of 16 individual cells for solitary confinement, which - delayed because of political resistance and that of an influential jailer - only opened its doors for prisoners in 1795/96.

[http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/laworder/policeprisons/overview/earlyprisons/ In 18th century Britain, e.g., more than 200 offences were regarded as serious enough to be punishable by death. Serious offenders who were not hanged were transported to the colonies, an alternative form of punishment introduced by an Act of Parliament in 1718.

Compared with its reformatory intentions the penitentiary was a failure. Unfortunately, that was not recognized by those in power, and when Walnut Street closed, its replacement - the ESP (1829-1971) followed identical solitary confinement principles. While ESP became a model for first the London Pentonville prison and later on for hundreds of prisons all over the world, people who actually walked into the ESP and talked with inmates, such as Charles Dickens, who visited in March 1842]], came closer to the truth.

Witness: Charles Dickens's "Philadelphia, and its Solitary Prison", American Notes, Ch. 7, 1842

Even though only a minority of inmates ever were housed in those solitary cells, and even though their real function was quite different from what the intentions had been, this penitentiary house started a revolutionary system of separate incarceration emphasizing principles of religious salvation rather than punishment - at least in theory.

First pioneered mostly by Quaker reformers, the penitentiary, unlike jails or prisons, set itself to the task of rehabilitating prisoners. Religious penance became the paradigm for criminal punishment; the monastic chamber served as the model for the prison cell. Walnut Street exemplified the philosophy of what became known as the Pennsylvania System, which separated prisoners from one another and hoped that solitude would facilitate repentance and transformation.

After conditions in the Walnut Street Penitentiary had become unbearable, it was deactivated in 1835 and later razed and prisoners were transported to the newly built Eastern State Penitentiary (1829-1971).

The Eastern State Penitentiary (aka ESP) in Philadelphia, Pa., operational from 1829 until 1971, refined the revolutionary system of separate incarceration first pioneered at the Walnut Street Jail's Penitentiary House, which emphasized principles of reform rather than punishment.

Pentonville Prison

A Short History of Solitary Confinement

Prisons were a relatively new concept in the early 1800s. Punishment for crimes had been a matter for communities until then. Some took the Hammurabian approach of an eye for an eye, and public hangings in town squares were the price for murder, rape, or even horse thievery. As a more nuanced judicial system evolved, civic leaders sought a more civilized method of punishment, and even began entertaining the idea of rehabilitation.

In 1790, Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia (built in 1773, but expanded later under a state act) was built by the Quakers and was the first institution in the United States designed to punish and rehabilitate criminals. It is considered the birthplace of the modern prison system. Newgate Prison in New York City followed shortly after, in 1797, and was joined 19 years later by the larger Auburn Prison, built in western New York state. All three were perhaps naive experiments in the very new concept of modern penology. They all began as, essentially, warehouses of torture. The gallows and stocks were moved inside, but little else changed. Those who survived generally came out as better-trained thieves and killers.

Between Philadelphia and New York, a schism in philosophies emerged: The Philadelphia system used isolation and total silence as a means to control, punish, and rehabilitate inmates; the Auburn or “congregate” system—although still requiring total silence—permitted inmates to mingle, but only while working at hard labor. At Walnut Street, each cell block had 16 one-man cells. In the wing known as the “Penitentiary House,” inmates spent all day every day in their cells. Felons would serve their entire sentences in isolation, not just as punishment, but as an opportunity to seek forgiveness from God. It was a revolutionary idea—no penal method had ever before considered that criminals might be reformed. In 1829, Quakers and Anglicans expanded on the idea born at Walnut Street, constructing a prison called Eastern State Penitentiary, which was made up entirely of solitary cells along corridors that radiated out from a central guard area. At Eastern State, every day of every sentence was carried out primarily in solitude, though the law required the warden to visit each prisoner daily and prisoners were able to see reverends and guards. The theory had it that the solitude would bring penitence; thus the prison—now abandoned—gave our language the term “penitentiary.”

Ironically, solitary confinement had been conceived by the Quakers and Anglicans as humane reform of a penal system with overcrowded jails, squalid conditions, brutal labor chain gangs, stockades, public humiliation, and systemic hopelessness. Instead, it drove many men mad.

The Auburn system, conversely, gave birth to America’s first maximum-security prison, known as Sing Sing. Built on the Hudson River 30 miles north of New York City, it spawned the phrase “sent up the river,” meaning doomed. Although far different from Walnut Street, Eastern State, and Auburn, in that inmates were permitted to speak to one another, in many ways it was the most brutal prison ever built. Various means of torture—being strung upside down with arms and legs trussed, or fitted with a bowl at the neck and having it gradually filled with dripping water from a tank above until the mouth and nose were submerged—replaced isolation and silence. Sing Sing also held the distinction of being home to America’s first electric chair.

Europe’s eyes were on the curious competing theories at Sing Sing and Eastern State. A celebrity at the time, Charles Dickens visited Eastern State to have a look for himself at this radical new social invention. Rather than impressed, he was shocked at the state of the sensory-deprived, ashen inmates with wild eyes he observed. He wrote that they were “dead to everything but torturing anxieties and horrible despair…The first man…answered…with a strange kind of pause…fell into a strange stare as if he had forgotten something…” Of another prisoner, Dickens wrote, “Why does he stare at his hands and pick the flesh open…and raise his eyes for an instant…to those bare walls?”

“The system here, is rigid, strict and hopeless solitary confinement,” Dickens concluded. “I believe it…to be cruel and wrong…I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain, to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body.”

In the late 1800s, the Supreme Court of the United States began looking at growing clinical evidence emanating from Europe that showed that the psychological effects of solitary were in fact dire. In Germany, which had emulated the isolationist Pennsylvania model, doctors had documented a spike in psychosis among inmates. In 1890, the High Court condemned the use of long-term solitary confinement, noting “a considerable number of prisoners…fell into a semi-fatuous condition…and others became violently insane.”

Prisons built after this period—including Angola—were designed more as secure dormitories for captive laborers, as envisioned in the Auburn system. Inmates were required to work together at prison industries, which not only kept them occupied; it helped the institutions support themselves. Sing Sing, for example was built on a mine and constructed entirely of the rock beneath it by inmate labor.

Eastern State was a grand failure, and it was closed in 1971, 100 years after the concept of total isolation was abandoned. But what it revealed about the torturous effects of solitary may have made the practice attractive to those less concerned with rehabilitation and more interested in retribution. Solitary in the 20th century became a purely punitive tool used to break the spirits of inmates considered disruptive, violent, or disobedient. But even the most retributive wardens have rarely used it for more than brief periods. After all, a broken spirit theoretically eliminates danger; a broken mind creates it.

But in the past 25 years, the penal pendulum has swung back toward the practices—absent the theories—that governed the “Philadelphia system” invented at Eastern State. We no longer seem to have faith in the “penitent” part of “penitentiary,” and our “corrections” system no longer “corrects” anti-social behavior but inevitably breeds it. It can be argued that today, almost all maximum-security prisoners in America are kept in a kind of solitary for a large portion of their sentences. The advent of “supermax” and “control unit” prisons in the early 1970s has led to the construction of pod-based prisons and “security housing units” in which all inmates are isolated one to a cell for most of every day. They are generally allowed out for an hour each day for exercise or a shower, and are permitted limited personal possessions and visits. Many of the newer prisons enforce the “solitary” aspect by keeping some prisoners in soundproof cells, so they cannot even talk or shout at one another. The lack of regular human contact is still considered inhumane by many rights advocates who have taken to the state legislatures and courts to challenge its constitutionality. Ironically, one of the loudest advocate groups is the National Coalition to Stop Control Unit Prisons—a project of the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker group.

Weblinks & Bibliography

- Skidmore, Rex A. (1948) Penological Pioneering in the Walnut Street Jail, 1789-1799, 39 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 167.

The Walnut Street Prison was a pioneering effort in prison reform. Originally built as a conventional jail just before the American Revolution, it was expanded in 1790 and hailed as a model of enlightened thinking about criminals. The prison, in fact, was known as a "penitentiary" (from the Latin word for remorse). It was designed to provide a severe environment that left inmates much time for reflection, but it was also designed to be cleaner and safer than past prisons. The Walnut Street Prison was one of the forerunners of an entire school of thought on prison construction and reform.

The prison was built on Walnut Street, in Philadelphia, as a city jail in 1773 to alleviate overcrowding in the existing city jail. Although designed by ROBERT SMITH, Pennsylvania's most prominent architect, the building was a typical U-shaped building, designed to hold groups of prisoners in large rooms. By and large the role of prisons was to incarcerate criminals. There was little regard for their physical well-being, nor were there any attempts to rehabilitate them. Prisons were overcrowded and dirty, and inmates attacked each other regularly. Those who served their sentences came out of prison probably more inclined toward a criminal life than they were before their incarceration.

It was the Quakers of Philadelphia who came up with the concept for what they called a penitentiary—a place where prisoners could reflect on their crime and become truly sorry for what they had done. The Quakers believed that through reflection and repentance, inmates would give up crime and leave prison rehabilitated. Shortly after the American Revolution, a group of Quakers formed the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, whose goal was made clear in its name. (Later the group became known as the Pennsylvania Prison Society.) In the years after the Revolution this group worked to encourage prison reform, and its efforts finally paid off in 1790 when the Walnut Street Jail became the first state penitentiary in the country.

The main addition to the Walnut Street complex was a new cellblock called the "Penitentiary House." Built in the courtyard of the existing structure, it included a series of small cells designed to hold individual prisoners. The cells and the corridors connecting them were designed to prevent prisoners from communicating with each other. Windows were high up (the cells had nine-foot high ceilings) and grated and louvered to prevent prisoners from looking onto the street. Each cell had a mattress, a water tap, and a privy pipe. Inmates were confined to their cells for the duration of their confinement. The only person they saw was the guard and then only briefly once a day. They were sometimes allowed to read in their cells, but for the most part they sat in solitude. The Quakers saw this solitary confinement not as a punishment but as a time for reflection and remorse. That was the reason the inmates were not put to work. Labor, said penitentiary proponents, would preoccupy the inmates and keep them from reflecting on their crimes.

The Walnut Street Prison became in part the model for what became known as the "Pennsylvania System" of prison design and philosophy. Other prisons built on the Pennsylvania model included a prison in Pittsburgh in 1821, the Eastern State Penitentiary (Cherry Hill) in eastern Philadelphia in 1836, and the Trenton State Prison in New Jersey the same year. The concepts of solitary confinement and repentance were key components of prison life at these institutions, although some Pennsylvania System prisons did introduce labor to the inmates. Visitors from overseas who were interested in prison reform visited Walnut Street, Eastern State, and similar prisons to see how they operated and to gain knowledge about prison reform strategies.

Meanwhile, in 1821 a prison was opened in the small upstate New York town of Auburn. That prison, which relied on individual cellblock architecture, required inmates to work 10 hours per day, six days per week. A number of prison reformers believed that by making the inmates work in an atmosphere free of corruption or criminal behavior, they would build new sets of values. The work would rehabilitate them because it would give them a sense of purpose, discipline, and order. This system became known as the "Auburn System," and it was followed in 1826 with the opening of Sing Sing prison on the banks of the Hudson River.

Soon it was clear that the Auburn system worked better at rehabilitating prisoners than the Pennsylvania system, and in the next century the Auburn system became the dominant one. Many prisons built to operate under the Pennsylvania System switched to the Auburn System. Vestiges of the Pennsylvania System exist in the philosophy of humane punishment, although no prison in the U.S. as of 2003 would place anyone in near-total isolation except in extreme circumstances.

As for Walnut Street, its success was short-lived despite the good intentions of the Quakers. The practical matter of housing prisoners became more pressing than the desire among prison officials to rehabilitate the inmates. Walnut Street became overcrowded and dirty, and there was no sign that isolated prisoners were being rehabilitated through solitude. By the 1830s the prison had outlived its usefulness, and it was closed in 1835. Later it was razed, and a library now stands on the site.

Built within the courtyard of the existing structure, it included a series of small cells for individual prisoners. The cells and the corridors connecting them were arranged to prevent prisoners from communicating with each other. Windows were high up (the cells had 9-foot-high (2.7 m) ceilings) and grated and louvered to prevent prisoners from looking onto the street. Each cell had a mattress, a water tap, and a privy pipe.

- The same year that America declared its independence from Great Britain, Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail opened. Its first major addition came in 1790 at the instigation of Quaker reformers who proposed “a penitentiary house” of sixteen individual cells for solitary confinement. The penitentiary, unlike jails or prisons, set itself to the task of rehabilitating prisoners. Religious penance became the paradigm for criminal punishment; the monastic chamber served as the model for the prison cell. Walnut Street exemplified the philosophy of what became known as the Pennsylvania System, which separated prisoners from one another while enforcing silence and manual labor as mechanisms for transformation.